Originally published April 3, 2013 at Fansided Radio:

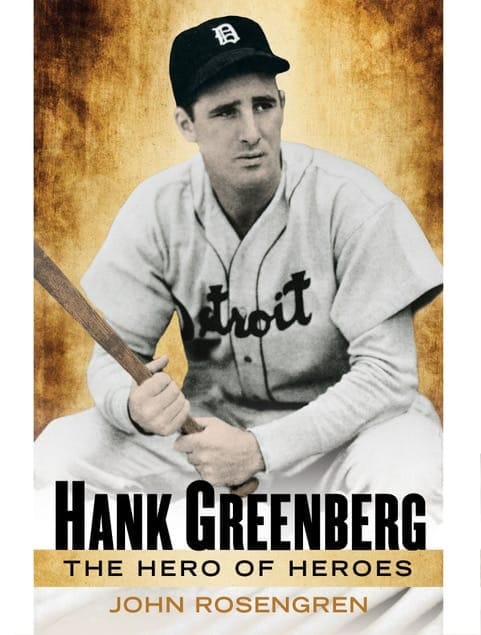

I spent the better part of the last week or so reading John Rosengren’s recently published book, Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes, to get ready for Opening Day.

In the last decade or so, we have seen biographies on Hall of Famers such as Sandy Koufax, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, Babe Ruth, and Lou Gehrig amongst others. But until this year, we had yet to see the premier biography of the first Jewish baseball star: Henry “Hank” Greenberg. Koufax is the greatest Jewish pitcher that has ever lived but Greenberg is the greatest Jewish hitter of all time.

Rosengren has done a heck of a job in covering Greenberg’s time growing up and the antisemitism that he dealt with while playing in the minor leagues and with the Detroit Tigers.

Take out the four years that Greenberg lost to World War 2 and who knows if he ends up with 500 or 600 home runs in his career. He enlisted early in the 1941 season and while other ballplayers that departed for the service continued to stay in athletic shape by playing barnstorming baseball games, Greenberg didn’t. Ultimately, he paid for that with his career when he came back from the war during the 1945 season. He played two more seasons and that was it. In an alternate universe where the war doesn’t happen and Greenberg maintained his averages, he could have easily had another 200 home runs.

Greenberg would go onto retire following the 1947 season to some amazing numbers: a .313 career batting average, 331 home runs, 1,276 RBI, 4 All-Star selections, 2 AL MVP Awards, 2 World Series wins, and induction into baseball immortality in 1956 when he was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

Greenberg the player, as we learn, is no different than Greenberg the executive–always looking out for his financial gain. If he had a great year, he thought he should earn some more money, no matter what the economic conditions were in the United States. As a general manager, if he thought a player had a down year, he saw to it that he wasn’t paid as much. Just look at what happened with Al Rosen. Two seasons removed from an MVP year and his career really wasn’t the same.

As a mentor, though, Greenberg helped tutor Ralph Kiner, a future Hall of Famer in his own right. Does he get to that point without Greenberg’s mentoring? I don’t know.

With the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers interested in signing Jewish ballplayers to appeal to the Jewish population of New York, many teams tried to find that Jewish ballplayer who would break through. The Yankees came close to signing Greenberg but he didn’t think he could beat out Lou Gehrig for the starting job at first base. He was right. Gehrig would stay there until ALS forced him to retire from baseball.

As a person, he welcomed the opportunity to sign Black players on the Indians or White Sox. Rosengren writes about how the cities reacted to his signing them. After Jackie Robinson died, Greenberg realized he should have done more for him when he first came up as a rookie.

Rosengren’s book shows how Greenberg was able to triumph over the adversity that he dealt with. If you are a fan of the Detroit Tigers, baseball, or a Jewish baseball fan, this book is for you.